The tragic story of the Death Railway in Kanchanaburi, Thailand

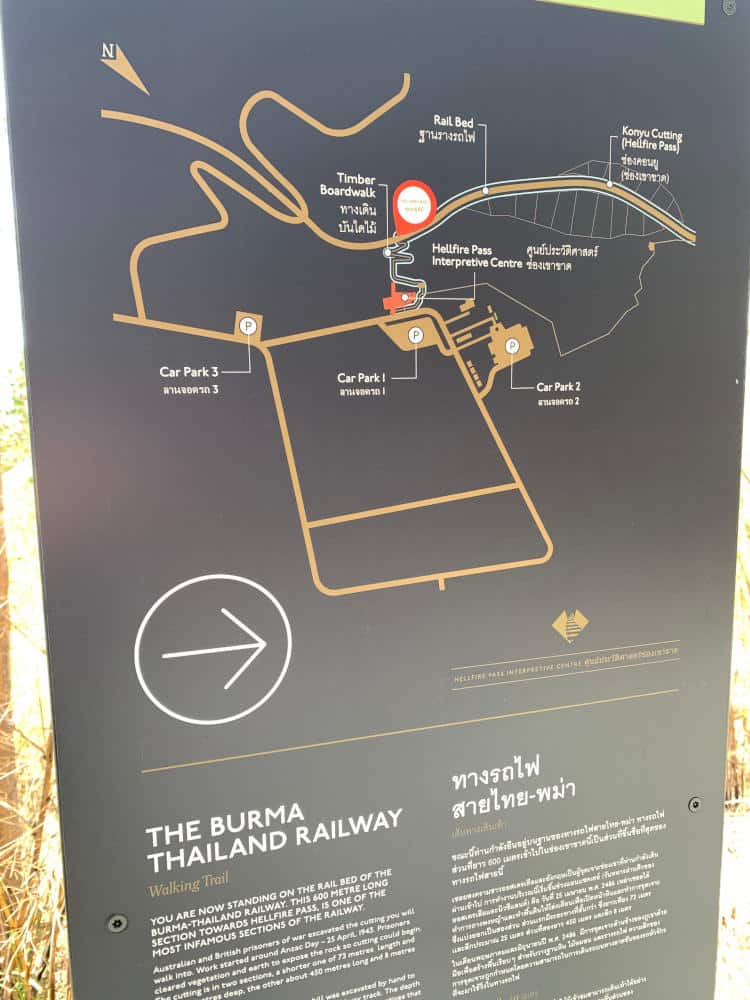

Having overnighted in the lovely BaanRai KhunYa, on the Kwae Noi river, we were following the GPS along the rather narrow Hintok Road and we discovered a small group of people under a covered bus stop. Inquisitive, we stopped and explored. To the right of the small road, there was a slight outline of a flat path, this was the end of the Death Railway and the people had walked the 2.6 kms from Hellfire Pass.

To the left of the road, there was nothing. Time, and the jungle had virtually removed any evidence of the continuation of the Death Railway and further north the Vajiralongkorn Dam has covered what remained under the vast waters of the reservoir.

The Burma-Siam Railway was constructed along the Kwae Noi river valley during World War II, to connect Bangkok with Moulmein (now Mawlamyine) in Burma (Myanmar).

Following to the surrenders in Singapore, Hong Kong, the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies, the Japanese forces had captured more than 140,000 Allied prisoners who were packed onto “Hell ships” and sent as forced labour around Japanese invaded territory. One in five prisoners did not survive these terrible, cramped and disease-ridden journeys.

Having lost two decisive sea battles, the Japanese realised that over-land routes were essential for their war plans and with an enormous pool of captive labour, proceeded to construct the Burma Railway. Between June 1942 and October 1943, the Prisoners of War and forced labourers constructed 415 kms of track from Ban Pong in Thailand to Thanbyuzayat in Burma. Eight bridges were constructed in addition to 600 trestle bridges holding the track firmly against the rock faces.

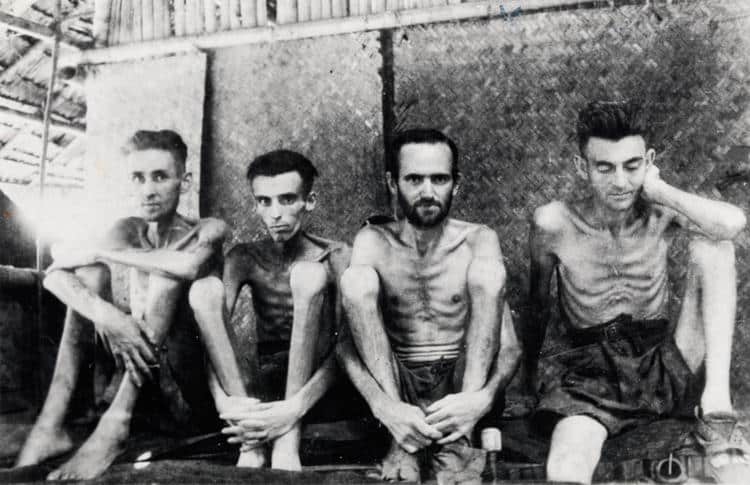

The need to have the railway completed as quickly as possible resulted in massive numbers of prisoners working simultaneously throughout the entire length. Conditions were atrocious through the mosquito infested jungle with uneven terrain whilst monsoon rains and summer heat compounded their suffering. Equipment was limited relying on inadequate hand tools and the brute strength of the undernourished prisoners and the viscousness of the guards to ensure progress.

It has a painful story. A peacetime estimate has suggested that it would take 5-6 years, but it was completed in just 15 months with a tragic toll of the loss of human life and is a testament to the astonishing capabilities of humans even under the most unimaginable circumstances. It is estimated that 60,000 allied prisoners worked on the railway in addition to tens of thousands of forced labourers.

Prisoners had to work up to 18 hours a day with inadequate food often no more than small portions of rice with contaminated vegetable or fish. Potable water was virtually non-existent resulting in many of the prisoners being malnourished and dehydrated. Combined with appalling camp conditions, this led to dysentery, diarrhoea, cholera and malaria.

To add to their misery, the brutality of the Japanese guards has become legendary. Due to the oath taken to their Emperor to die rather than be captured, their mentality could not comprehend surrender and treatment of the prisoners reflected this. It is estimated that more than 12,500 Allied prisoners of war died in addition to tens of thousands of forced labourers. To compare, 27% of all POWs in Japanese hands perished in contrast to just 4% in German camps.

Today, the railway is a testament and lasting memory to all the prisoners who either died or carried the scars for the rest of their lives. Trains still run from Kanchanaburi, over the infamous ‘Bridge on the River Kwai and along the cliff-hugging trestles of the Wang Po Viaduct above the River Kwae Noi and as far as Nam Tok.

Approximately 80 kms north of Kanchanaburi is the Konyu Cutting, better known as Hellfire Pass. Nothing can prepare you for the eyrie feeling of walking alone along this cutting. At 75 metres long and 25 meters deep it is a sad testimony to the thousands who were forced to work here both day and night to complete construction in just 12 weeks. Whilst no track remains, the site is now well preserved by the Australian Government’s Hellfire Pass Memorial Museum. The tree that has grown in the pass emphasises the depth and is a poignant reminder to the intense suffering and degradation that took place here.

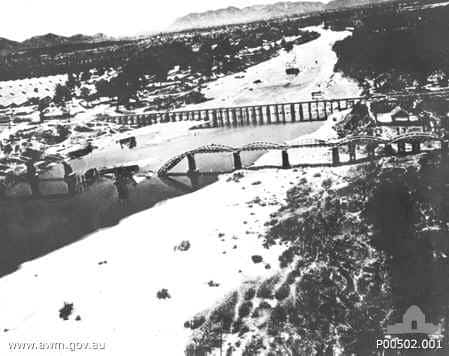

Debunking some myths: – The famous movie The Bridge on the River Kwai was based on Pierre Boulle’s 1952 novel and directed by David Lean in 1957, was a stirring film loosely based on the exploits of Lieutenant Colonel Philip Toosey. Charged with building Bridge 277 over the then called Mae Klong River, Philip Toosey was portrayed as a collaborator with the Japanese when, in fact, he worked tirelessly to ensure that as many of the prisoners could survive. Much was also done to attempt sly sabotage to the bridge which included collecting termites to eat through the wood.

Two bridges were built. First a temporary wooden construction then a few months later the permanent steel and concrete bridge in 1943. This had been transported from Java in the Dutch East Indies and was used for 2 years before being severely damaged by allied bombings in 1945.

This repaired bridge is the one that we see today was re-constructed by donations from Japanese reconciliation funds. Following the success of the film and subsequent number of tourist arrivals to Kanchanaburi, the name of the Mae Klong River was changed to the River Kwai (Kwae Noi) in 1960.

Thailand’s Role in WW2 – Thailand had managed to avoid being Colonised but was surrounded by the colonial states of Burma (Great Britain), Laos, Cambodia & Vietnam (French Indonesia) and Malaya (Great Britain). Thailand officially adopted a position of neutrality until the 5-hour invasion of the country in December 1941. This short skirmish led to an armistice and military alliance treaty.

At the commencement of the Pacific War Japan pressured the Thai government to allow passage of Japanese troops for the planned invasions of Burma and Malay. As an ally of the Empire of Japan, Thailand was able to retain control of its armed forces and internal affairs and annexed territories expanding north, south and east, briefly gaining a border with China near Kengtung.

Politically split between the Phibun regime and the Free Thai Movement, Thailand survived relatively unscathed with only slight damage from allied bombing. Thailand registered 5,569 military deaths, mostly due to disease and less than 500 in military action. The Free Thai Movement was a well organised pro-Allied resistance movement of around 90,000 supporters/guerrillas. This movement provided espionage services to the Allies and some sabotage activities throughout the country.

An example of the bravery of local resistance was Boonpong Sirivejjanhandu a local Kanchanaburi merchant, who was able to use his cover as a supplier to the camps to smuggle much needed medicine and other supplies.

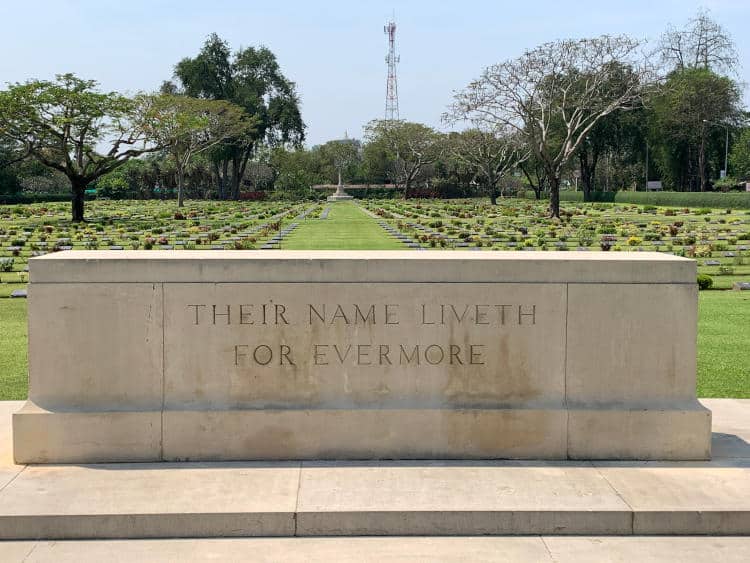

Reconciliation:- At the end of the war some survivors remained to assist the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to identify the temporary graves, many of which were in the jungle along the track. Remains were identified and finally laid to rest in two War Cemeteries. The Kanchanaburi War Cemetery (Don-Rak War Cemetery) contains 6,982 graves of British, Australian, and Dutch prisoners with 6,858 being identified. At the Chung Kai War Cemetery are the remains of a further 1,426 British and 313 Dutch prisoners.

Kanchanaburi Today:- The area has become a major tourism destination being just a two hour drive from Bangkok with an estimated 8 million visitors per year(pre-Covid). Whilst the attraction for many is the Death Railway it also offers many places of interest, including the famous Erawan Waterfalls and hotels located on the river. Whilst the infamous bridge is normally overrun with tourists the War Cemeteries remain dignified and beautifully attended to.

The JEATH museum has recreated the barracks and one can appreciate how appalling the conditions were. A visit to the Death Railway Museum and Research Centre is highly recommended to gain an appreciation of the complexity of the railway and the poor POWs conscripted to build it in such short time.

There is an exhibit that shows the Hellfire Pass construction. It is a scene from Hell (hence the name) and when visiting Hellfire Pass one can appreciate the appalling conditions suffered by the unfortunate individuals condemned to such brutal treatment.

The more recent film, “The Railway Man” depicts the terrible conditions and the long-lasting trauma effects that haunted many of the survivors. It is an excellent performance by Colin Firth who is finally able to lays his ghosts to rest and met with a former prison interpreter. The lasting message is one of reconciliation.

The story of The Death Railway is a sad one considering the massive suffering and loss of life not only to the POWs but also to the thousands of forced labourers. Whilst the two main War Cemeteries and other memorials commemorate many, thousands have no monument to their toils and demise. When you visit Kanchanaburi please respect the reason why this all exists and what happened here.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.